Spawning giant clams for livelihood

The fascinating island of Semirara in Antique has modern facilities, attractive brick-lined architecture, a coal mining pit, profusion of flora and fauna amid a maze of crisscrossing dusty roads, man-made lakes, a marine sanctuary, and a new but quaint-looking chapel near a gently rolling hillside with life-size Stations of the Cross.

The 5,500-hectare island has a population that has almost doubled to 17,000 in the last seven years. The main livelihood of the people is mining, deep sea fishing and, to an extent farming, although the soil is not very fertile, being mostly lime.

The island is home to the Consunji-managed Semirara Mining & Power Corp. which developed and maintains the Semirara Marine Hatchery Laboratory. Here, at the idyllic Tabunan Beach Cove with its white sand, limestone walls and wild vegetation, giant clams are being spawned, collected and will eventually be commercially available.

Genesis

The project has its genesis in the environmental rehabilitation and community resiliency programs of Dr. Edgardo Gomez, a national scientist and professor emeritus at the University of the Philippines-Marine Science Institute (MSI).

Article continues after this advertisementMSI “was one of the partners which involved Pacific Island countries, such as Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Tonga,” recalls Gomez. “The two main objectives were to restock and rehabilitate reefs with the various species of the giant clams and to develop a livelihood for coastal dwellers.”

The giant clams can help clean seawaters, being filter feeders.

“The work being done in Semirara is very significant in marine resource conservation and biodiversity enhancement, not only in the Philippines but also in Southeast Asia,” Gomez says. “The private sector should continue to play a key role in promoting the sustainability of our marine species, promoting both conservation and managed production that can contribute to livelihood improvement of coastal populations.”

The Semirara Marine Hatchery Laboratory reached a new milestone in June 2014 when Gomez linked the hatchery laboratory with the Marine Ecology Research Center (MERC) of Sabah, Malaysia.

Through the linkage, Semirara was able to acquire from MERC 150 juveniles and three broodstock of Hippopus porcellanus in exchange for the same number of T. gigas from the Semirara marine sanctuary.

Environment agent

- porcellanus from Malaysia completes in the Philippines the seven species of giant clams of the tropical regions.

Gomez lauded the recent exchange between Semirara and Sabah, emphasizing the importance of scientific research on the giant clams in marine life conservation. In this way, Semirara Mining Corp. can play a key role as a positive environment agent.

The Semirara Marine Hatchery Laboratory maintains working partnerships with leading institutions and personalities to contribute to the effort to revive the Philippine marine biodiversity.

It has worked with Dr. Suzanne Mingoa-Licuanan, also of UP-MSI, sharing best practices and technical resources for research purposes. In 2013, the hatchery laboratory traded 600 juveniles of T. gigas and 400 juveniles of T. squamosa for 10 T. gigas broodstock with MSI, which was in need of juveniles.

Another eminent marine biologist and national scientist, Dr. Angel C. Alcala, a former DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) secretary, has visited the facility and expressed strong support for the company’s initiatives in rehabilitating the Semirara coast through its work on giant clams and other present wildlife.

The area has to be rehabilitated due to overfishing and destructive fishing methods.

The phrase “giant clams” is just a common name, generic.

The smallest is Tridacnacrocea at 15 centimeters, while the biggest is Tridacnagigas, which grows up to more than one meter. The Tridacnagigas is the biggest species of giant clams. The other species being spawned are Hippopushippopus, Hippopusporcellanus, Tridacnacrocea, Tridacna maxima and Tridacnaderasa.

The facility is also propagating another marine product, the expensive abalone. The laboratory is also experimenting on the South Sea pearl oyster.

‘We spawn, we grow, we reseed’

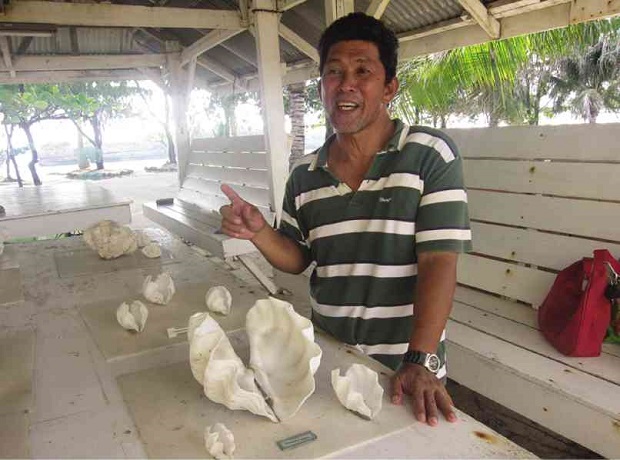

The laboratory is headed by Dr. Ronnie P. Estrellada, a noted marine biologist from Tagum City, Davao del Norte, who trained on giant clams’ hatchery and culture under Licuanan.

“We spawn, we grow, we reseed the endangered giant clams, all seven species that can be found in the Philippines and Southeast Asia,” Estrellada says during an interview. “It’s our strategy for marine environmental rehabilitation in this part of the globe.”

Spawning started in 2011 and, in the first test, some 4.7 million fertilized Tridacnagigas eggs were spawned, says Estrellada.

The giant clams are hermaphroditic; they are male in the first five years of their life, and then they are able to produce both sperm and egg.

Serotonin (which costs P50,000 per 20 grams) is used to induce spawning, which has resulted in 80,000 giant clams in the marine sanctuary of the island.

The agreement with the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) regarding the breeding of the giant clams (along with other forms of aquatic wildlife) is that 70 percent can be allotted for commercial purposes, while the remaining 30 percent will be retained for conservation.

“You cannot go on with this very expensive project unless you eventually sell,” Estrellada quoted BFAR Director Asis Perez as saying.

Clams don’t come cheap

So the time will come when some two-thirds of the giant clams will have to be sold, so as to keep the project going. No word on the prices yet, but these won’t come cheap. The possible customers include aquarium collectors and resort owners who are keen on the product, which can be for decoration or for consumption.

The meat of the clams is said to be delicious.

Options for grow out are being considered as additional livelihood for the community members.

“Combined efforts, including private sector players, are required to ensure sufficient stocks for natural reproduction,” Gomez observes. “Sanctuaries can be established where broodstock of the different species can be grown and protected. Excess clams can then be seeded in suitable areas to enhance biodiversity and the productivity of these coral reefs and related ecosystems. Marine parks and tourist diving areas should be the initial targets for restocking.”

The company encourages residents to visit the Semirara Marine Sanctuary. The hatchery laboratory is a highlight of mine tours given to island guests.

From April to May 2012, the facility’s marine biologists and aqua technologists played host to Semirara Summer Campers who were given hands-on experience in marine life studies and protection. They even let them assist during spawning of the giant clams.

Since the school year started, about 200 local students have visited the hatchery laboratory.

The young adults of Semirara now understand why they should, for the time being, leave alone the giant clams in the sea. They say they did not think marine conservation could be so much fun.