Midwives deliver as entrepreneurs

Olive, Marilou and Melanie have something to sell as franchise holders—and it’s not hotdogs, mineral water or beauty salon services.

The three are licensed midwives, part of a growing network of franchisees under the social franchising for health program for emerging small entrepreneurs.

Unlike the traditional franchising system that hands down successful business practices to one willing to adopt a brand’s concept and systems, social franchising exists not just for the profit motive but also a social purpose.

On Oct. 23, the second Global Conference on Social Franchising for Health opened in Cebu City, with the aim of sharing knowledge and best practices with partner implementers, donors, experts and policy makers.

Among other topics, the conference will zero in on the role of social franchising in the delivery of affordable and quality maternal healthcare, as seen from the experience of people like Olive, Marilou and Melanie.

The conference, which ends today, has drawn representatives from 40 countries (the first meeting took place in Kenya in 2011). It was organized by the Private Sector Healthcare Initiative of the University of California San Francisco Global Health Group.

Population Services Pilipinas Inc. (PSPI), one of the participants, for example, will talk on the impact of its BlueStar Pilipinas clinics, a family planning franchise run by midwives, on improving equitable access to high quality maternal and family planning services through their franchisees, especially in underserved populations.

“We also want to share the experience of BlueS tar Pilipinas with the global social franchising community regarding the sustainability of our services through the accreditation of midwife-franchisees as providers of Philhealth’s Maternity Care Package,” said PSPI Chief Executive Virgilio Pernito.

The Philhealth coverage for mothers about to give birth is also a boon for the participating midwife in the BlueStar social franchise who gets almost double the usual delivery fee (from P3,500 to P4,000) paid to her by the patient.

BlueStar opened its doors in 2008 to largely marginalized women in need of maternal care. There are 196 BS clinics in Luzon, 33 in the Visayas and 37 in Mindanao.

The midwives’ stories from a series of unfortunate events to fairytale endings as successful franchisees are straight out of a sudsy soap series.

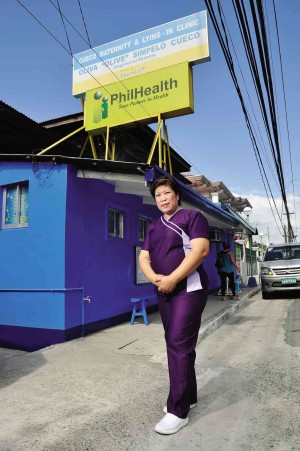

Olivia Cueco runs her clinic located on a busy street in a busy commercial area of General Trias, Cavite province. She has come a long way from toiling as a washerwoman for relatives who paid her back by sending her to a school for midwives. “Yung mabayaran ako ng P30 para maglabada, tuwang-tuwa na ako,” (A P30 fee for washing clothes was enough to make me happy”), recalled the loquacious Cueco.

Today, the enterprising midwife shows no traces of her former life as she reigns in her Gen. Trias roost, a three-story aerie one would easily mistake for a similar facility in a mall: fully air-conditioned, with a giant LED television set, a sound system that plays soothing music and a well-stocked refrigerator and pantry.

Before she found out about BlueStar, Cueco serviced mothers about to give birth in their homes, earning anywhere from P300 to P500 per delivery, “kung minsan, hulugan o libre” (sometimes patients paid by instalment or not at all).

Once, a friend invited her to attend an orientation program in search of midwives who could run clinics “the BlueStar way.” That meant undergoing rigid training on family planning methods, counseling, clinical skills, office procedures and marketing techniques. Lured by the promise of a raffle and good food at an exclusive beach resort where the program was held, Cueco stayed on to listen, and liked what she heard.

“I couldn’t believe the spiel at first,” she admitted. “Who in his right mind would offer to help build you a clinic, complete with equipment. Then you are monitored regularly to see if their standards are met. In between were continuing education courses. All I had to look for was a location. They even give you your own calling cards!”

It wasn’t hard to find a spot—a vacant lot owned by her parents where they had a makeshift food stall that served merienda fare. BlueStar provided the rest: helping build the clinic, including putting up the BlueStar yellow and blue signage with her name on it.

Once she set up shop, she could hardly keep the women from coming.

Cueco, who is often called “doktora” (doctor) in the community, said it was probably because she takes a personal interest in her patients, often spending more time than necessary with each. “The women said the health center or public hospital staff were “masungit” (crabby) or ignored them. “Maasikaso kasi ako (I attend to them),” she said, explaining her popularity with the moms.

Seventeen years after delivering her first baby “pro bono,” Cueco is not about to stop dreaming. “I’m thinking of expanding my clinic so I can hire a medical technologist for a laboratory I want to set up,” she said. “BlueStar has shown me the way.”

Just like Cueco, Marilou Monta had a rough ride on the way to the bank.

The sixth of 12 siblings, Monta originally wanted to be a “secret agent.” The plan was derailed when she got married and moved to Bagong Silang in Caloocan City with her husband. She decided to follow in her sister’s footsteps and became a midwife instead.

The choice couldn’t have been more appropriate.

Bagong Silang in Caloocan City is the biggest barangay (of 188) in the National Capital Region, with a burgeoning population of 1.5 million. The baby boom easily led to a birthing facility boom, with lying in clinics and birthing homes springing up like mushrooms in the closely-knit community. “There were maternity clinics everywhere. The competition was tough,” she said.

Her BlueStar training paid off, as word-of-mouth advertising brought curious housewives to her tiny clinic sitting in the middle of a bustling public market to see what made it different from the rest. “For one, it has a tidy and non-intimidating look. The mothers soon got over their shyness “kasi madaldal ako” (because I can talk up a storm) and started asking questions,” she said.

Apart from introducing them to different methods on how to plan their families, the women—even their husbands—are given counseling or advice, including referring them for ligation or vasectomy, as the case may be.

Those wary about visiting the clinic for the first time are invited to a “buntis” party (a party for pregnant women), a BlueStar “special.”

Guests are recruited by Marilou and Mary Jane Abordo, a BlueStar Field Management Team Member of PSPI, who make calls in households where they know there is a mother-to-be, and are told to gather at the basketball court. Single ladies preparing for marriage and teen moms are welcome.

Marilou, a midwife for the past 17 years like her BlueStar batchmate Ceuco, brings her “props” to show the various methods of family planning using visual aids and light banter, encouraging the women to participate. To make sure she has all her bases covered, Marilou talks not only about pills, condoms, injectables and IUDs but also on the natural planning method endorsed by the Catholic Church.

To find out if the one-hour lecture-demo was understood by each participant, Marilou and Mary Jane conduct a mini quiz show at program’s end, with prizes for the winners.

“It’s all in a day’s work,” said Marilou, who has been busy lately knocking down a wall of her clinic to build another room that would accommodate the influx of moms seeking her services.

Another successful franchisee, Melanie Bulanadi, operates a BlueStar clinic in Arayat, Pampanga province.

Bulanadi wanted to be a doctor, but the astronomical costs of going to med school made her re-think her choices. After enrolling in a BS psychology course, she dropped out in her third year and opted to be a midwife, working initially as a volunteer shortly after graduation. “It was tiresome, but I wanted to work in a hospital setting for the experience,” she said.

Newly-married then, Bulanadi has gone through hell and back. “We had no money and the debts were fast piling up. We had to hide from moneylenders! ”

Learning about the BlueStar franchise, she did not think twice and signed up for the one-month training program. Quick to take advantage of an opportunity when she saw one, she sold hand-crafted slippers to her batchmates.

After she got BlueStar’s go signal, she sought a contractor to build the clinic, and soon enough opened as fresh paint dried up on the walls. Rounding up the housewives of Barangay Bitas in Arayat where her clinic stands, she enticed them to visit “even just for a chat.”

In one year, Bulanadi was seeing 10 patients a month. That number has quadrupled, with almost 10 deliveries a week recorded in her ledger now.

“Maybe it’s because I apply what I learned as a psychology student to whatever I do when I reach out to patients. They say that talking to me is like talking to a friend. The best compliment is when they say: “Magaling na, mabait pa, at saka mura! (She’s not only good, she is nice and also comes cheap!)

Like most BlueStar franchisees, Bulanadi can now dream big.

Bulanadi has been buying equipment—an ultrasound machine, new beds, three airconditioners—for an ambitious project she hopes she can start soon.

“I want to own a primary hospital. I can be the administrator. That is my ultimate goal,” she said. “BlueStar made all my dreams come true.”