Activist executives say: ‘Never again!’

Someone once said: “If you are not an activist when you are young, you have no heart; but if you are still an activist when you grow up, you have no mind.”

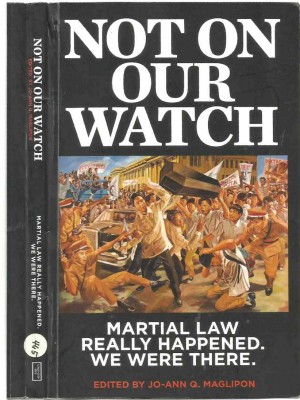

The above statement is effectively debunked by a book titled “Not on Our Watch,” edited by Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon.

Subtitled “Martial Law Really Happened. We Were There,” the book is a collection of remembrances by campus editors at the height of the Martial Law regime in the seventies—recalling the institutional violence imposed on the Filipino people in all its horrific and deadly forms.

It turns out these campus editors, 40 years ago, all members of the College Editors League of the Philippines, have lived to tell the sad and tragic story from the perch of their exalted or successful offices.

The activist’s fire burns in the hearts of the contributors to this anthology of stories.

These writers continue the task of “remembering,” as columnist Conrad de Quiros puts it.

“Time has a way of making us think of those who lived and died then as abstract figures or cardboard characters, who were just communists to the unsympathetic or larger-than-life figures looking death in the eye to the sympathetic. They were not, or not always so,” he said.

De Quiros underscored the value of remembering so much sacrifice, recalling their courage amid torture and pain, and relishing the thought of liberation.

Diwa C. Guinigundo, deputy governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, recalls: “What struck my spirit was the students’ steadfast profession of their cause, even as their heads and bodies were mauled by rattan and pummeled by the fists of law enforcers … That was the genesis of my search for meaning of the student movement.”

The student Guinigundo credits the First Quarter Storm (FQS) as one that “opened the floodgates of social consciousness” among students and the rest of the protest and activist movement.

“The FQS will always be a memorial to the struggles that must continue to be fought to bring about a more decent, more just, and a more respectable society.”

The activist streak remains.

Former Health Secretary Manuel M. Dayrit, an Atenean and then a UP medical student, channeled his activist energy through medical missions.

He was of course exposed to the doctrines of the protest movement and was influenced by the First Quarter Storm.

He recalls:

“The activism we practiced in medical school did not involve rallies in the streets. Rather, we were preoccupied with thinking about how to improve health care for millions of Filipinos, particularly the poor,” Dayrit says in the book.

He has seen the fall—even death—of fellow activists in the field, whose only fault was to treat the wounds of anyone, regardless of their political or ideological persuasion.

“I had classmates who were also working in other parts of the country and facing the same risks,” he says. “My classmate and friend, Dr. Bobby de la Paz, and his wife, Dr. Sylvia Ciocon, worked in Samar. Bobby was murdered in 1982 in his clinic in Catbalogan, Samar.”

The activist light continues to shine through the once seared soul of the former Health Secretary.

Al Mendoza, former sports and motoring editor of the Inquirer, and now columnist of a number of newspapers, declares in his article in this book: “I see, I forgive, I forget.”

Al was arrested and manhandled by the local police in his hometown, Mangatarem.

If not for the intervention of a local mayor, Al would have stayed long in jail for his activist roles when he was a college student and campus paper editor.

This Palanca awardee for fiction writing writes what was real during the onset of martial law, how his rights were violated, how he played “hide-and-seek” with the Marcosian forces.

When he tried to report to the Philippine College Commerce (PCC), a day after martial law was declared, Al began living dangerously.

Will Al forgive and forget? He says, “I see Marcos in 2012 as I saw him in 1972—as nature’s biggest mistake.”

And yet, Al—after forgiving a lady guard who earlier confessed that it was she who reported his activities—declares: “All I can say is letting go of an evil like Marcos is tantamount to making me feel like I have been released from a prison cell.”

Roberto Verzola, an electrical engineering graduate of UP Diliman—and now an expert on technical matters in a cause-oriented group—has taken some time to recall his harrowing experience in the hands of his torturers.

Verzola recalls: “Until then, I had no idea that a soft-drink bottle could be used for torture. I was made to squat inside a room with the air conditioner full turned on, and the session began. What I got were not the hard body blows that I had endured in ISAFP, but sharp taps on my limbs with a soft-drink bottle.

“They brought instead a gradually growing numbness that became an ache that grew sharper as muscle, tendon, ligament began to get sore and the skin became even more sensitive to pain. The taps weren’t done in a hurry. In fact, they came at a deliberate pace.”

Shall all these be forgotten? Verzola thinks not: “When we of this generation go, our memories should not leave the world with us. No, we must not forget.”

In this book, executives in business and non-business organizations look back—not in anger—over the atrocities of a dictatorship—but with concern that this darkest chapter might be forgotten. The next generation should not be given a “sanitized” version of martial law. The battle cry remains: “Never again!” dmv.communications@gmail.com

`