A journalist laughs as she recalls what several of the soldiers imprisoned for their alleged involvement in the assassination of former Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino had at the top of their wish list—when or if they were released: A meal at The Aristocrat restaurant.

Though funny, it is not so surprising. A married couple, both journalists, make sure that at least once a year they visit The Aristocrat, the one place they could easily afford to go to during their courtship, and the venue for many romantic dinners a deux.

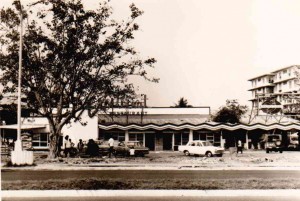

Now 78 years old, counting the years when it was just a mobile food seller shuttling around Manila’s main streets in a battered automobile, the modest eatery that serves lutong-bahay fare has become both a real and imaginary landmark in the lives of many Filipinos in and out of Metro Manila. And it continues to be the backdrop and venue for many Filipinos’ important milestones—weddings, baptisms, graduations, family reunions, homecomings—or for just a fun day or night with kith and kin.

Before Pinoys developed a taste for fried or inasal chicken, a serving of Aristocrat’s classic chicken barbecue, served with Java rice and atchara, was what eating out was all about. The hototay soup, a derivative of a Chinese dish that has since been dropped from the menus of many Chinese restaurants, remains a favorite meal starter—hot and invigorating.

While many diners forego dessert in other places, many Aristocrat patrons just have to stay and savor the Torta de los Reyes, chocolate-covered sans rival that reportedly even some teachers of St. Scholastica’s Academy in Marikina City want delivered with other menu favorites.

Many of its contemporaries—or even much younger “challengers”—have folded up, downsized or slowly faded into oblivion, but The Aristocrat remains, standing on property that is not even its own but leased long-term, a place of nostalgia and for making new memories.

Priscilla Reyes Pacheco, Aristocrat president and granddaughter of founder Engracia “Aling Asiang” Cruz-Reyes, believes the effort the whole clan exerts to protect The Aristocrat tradition and protect her grandmother’s legacy may be an important reason for its longevity. The founding matriarch, a housewife who went into the food business to augment her husband’s modest income as a government employee (Alex. Reyes, with the period after the first name, would become an associate justice of the Supreme Court), once declared, “I like to treat my customers the way I treat my family.”

The care, dedication and, of course, love she had for her 12 children were shared with the thousands of patrons who had celebrated memorable events, enjoyed downtime with family or simply eased hunger pangs at The Aristocrat.

Pacheco says there have been pressures to “update and upgrade” to keep up with new market players, but the family maintains Aristocrat should be the pacesetter.

“Ang Aristocrat ay ‘di gumagaya. Tayo ang ginagaya (The Aristocrat does not copy what others do, but others copy what it does),” she says.

Now a family corporation, the current Aristocrat board consists of Aling Asiang’s grandchildren and a surviving son.

While Aristocrat will not deign to copy what others are doing, competitors have not hesitated to try to replicate the restaurant’s winning ways, particularly the iconic chicken barbecue—some even brazenly called it Aristocrat-style chicken barbecue—but have fallen short of the standard.

New and reinvented restaurants may also brag about their chefs, but The Aristocrat still calls its kitchen staff cooks. Although The Aristocrat has opened a culinary school that offers diploma and certificate courses, training for the restaurant’s cooks remains primarily by apprenticeship or on-the-job in the kitchen.

The menu has also remained practically unchanged, perhaps another reason for patrons’ continued loyalty. Whether one has been away for a week or decades, he or she can count on his/her favorite dish will still be served at The Aristocrat. The only major additions, introduced in the 1970s, are the pastries made by The Aristocrat’s own bakeshop.

Pacheco says food has really been part of the family lifestyle, but knowing how to eat appears to be more useful to them than knowing how to cook. While not everybody can cook—the men seem to be more comfortable whipping up dishes than the women—everybody “knows how to eat.” Quality control for The Aristocrat has become the responsibility of each member of the clan, Pacheco says.

While she or her cousins may not know what goes into which dish, Pacheco says, they know how it should taste, and can tell if something is amiss. When dining at any of the seven Aristocrat branches, every Reyes family member ensures that standards are observed and maintained. Pacheco gets instant feedback if anything is not up to traditional Aristocrat quality.

Aristocrat also ensures that quality and standards are maintained in the few franchises that have opened outside Metro Manila by providing the raw materials.

Reynaldo “Nandy” Pacheco, gunless society advocate and the Aristocrat president’s husband, says the restaurant’s clientele transcends age and income groups. Ever the tireless campaigner, Nandy has labeled Aristocrat’s patrons as AWL—all walks of life—and the high, low and the mighty. Imelda Marcos, former First Lady and now a congresswoman representing Ilocos Norte, is as likely to drop in without any advance notice as a group of government prosecutors, even sitting judges and justices.

The Aristocrat is also one place where parents can readily bring their children without worrying about finding something kids will like to eat. People of all ages seem to enjoy the chicken barbecue, ordering it for breakfast, lunch, dinner and any time in between.

While 24/7 service is still a rarity, The Aristocrat on Roxas Blvd. has been open 24 hours, seven days a week for decades. In fact, Pacheco says, their busiest day of the year has always been Maundy Thursday, when the Catholic faithful, after doing the traditional lenten Visita Iglesia (a visit to seven churches), show up in droves. Even Good Friday is not a day of rest for the Aristocrat staff, as a sizeable crowd still shows up in the restaurant. The Jupiter branch, which services many call centers, is now also a 24/7 operation.

Perhaps the only concessions to the demands of today’s diners, who often have to hold “working” lunches and dinners, are the function rooms that can be expanded or “shrunk,” depending on the need, which Pacheco has added to the refurbished and renovated Aristocrat. There is also a ballroom for groups wanting to be separate from regular clients.

Last year, The Aristocrat finally got a formal recognition of its landmark and heritage status among Filipinos. The National Historical Commission put up a commemorative plaque marking The Aristocrat site on Roxas Blvd., Manila. It briefly describes The Aristocrat’s evolution from an old automobile going around the main streets of the capital to becoming one of the famous restaurants showcasing Filipino cuisine.