MANILA, Philippines–If integration of members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) is not in President Aquino’s State of the Nation Address on Monday, it should be.

In 2015, Asean Free Trade Agreement (Afta) will come into full effect. Signed among Asean members in 1992, the agreement anticipated a fixed period of downward preferential tariff adjustments among the members until those tariffs came down to zero.

What is Afta? What benefits shall we derive from it? How can we maximize the benefits for the nation? These are weighty questions.

The Asean was founded in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Being all geographically close neighbors, they closed ranks to form a political shield from the great uncertainties of the period: the Cold War and the escalating Vietnam War.

In Bali in 1976, Asean summit leaders turned to economic matters and directed their economic ministers to meet regularly to discuss cooperation in economic fields—agriculture, energy, transportation, tourism, finance, investment and trade. This led to progressive, small steps in different directions.

One of the most significant agreements to come out of these meetings was on trade cooperation. The coverage of the initial preferential tariff agreements was narrow and incremental, starting in the late 1970s. These early meetings established greater trust and mutual confidence among the members.

There were coincident developments that encouraged deeper Asean tariff preferences. The multilateral trade negotiations of the period were culminating in the reduction of world tariff barriers in trade. Regional trading blocs elsewhere were being formed. In Europe, the Common Market widened to include more countries. And, finally, the World Trade Organization was in its final round of negotiation to become the world trading regulator.

Leaders of the 10-member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations at a summit in Brunei. AFP FILE PHOTO

Free trade area

When Afta was signed, all the Asean countries committed to reduce their commercial tariffs toward zero by 2015, so that all tariffs between them disappear.

Deep preferential tariff cuts were made starting in 1992 and ending in 2015 when all members of the Asean will constitute a single market as far as trading with each other is concerned.

In achieving mutual free trade among the members, each of the countries will retain their external system of tariffs for all other countries. Those individual external tariffs were frozen toward certain agreed levels among the Asean countries during the Afta negotiations. Essentially, however, the individual external tariffs represented the member-country’s sovereign policy.

An effect of these external tariff negotiations was the universal reduction of protection rates among the Asean countries though they differ according to their own policies.

Asean economic market

Afta was motivated by efforts to:

1.) Increase the Asean’s competitive position as a production base in the world market through the elimination within the group of tariff and nontariff barriers; and

2.) Encourage more foreign direct investments (FDIs) to the Asean. When achieved, both objectives would further stimulate regional economic growth and, consequently, raise per capita incomes and living standards among the constituent nations.

As soon as the Asean began to negotiate regional cooperation agreements, major economies of the world took notice. After Afta was concluded, the Asean became even more important in their radar. The inflow of foreign capital in selected countries became even more profound and significant.

When Afta was concluded in 1992, it had six signatories, since Brunei had already joined the Asean. In 1995, Vietnam joined, followed by Laos and Burma (Myanmar) (1997) and then Cambodia (1999).

The latecomers to the Asean were required to be signatories to Afta, but they were given longer time for adjustments in order to meet the tariff reduction obligations.

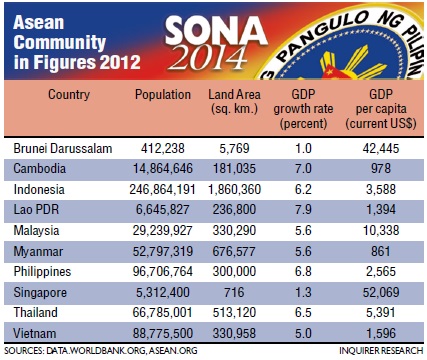

The 10-member Asean market (in 2012) has a population of 670 million people, with an average gross domestic product (GDP) per head in (purchasing power equivalent) current US dollars of 8,369. Although this level of GDP is not very high, the Asean countries belong to the most dynamic group of developing countries in recent years.

Papua New Guinea and East Timor, newly independent neighbors, are active regional observers, meaning, they could become members in the future.

When a free trade agreement is forged, the countries forming the region extend their economic market reach by the creation of a single collective market. It is simply aggregating all country markets into one big market. Larger trade creation is the most likely result and in the Asean case, this was the outcome.

This is game-changing for all participants. There are enormous economic implications on all countries. For instance, from a Philippine viewpoint, the “domestic” market expands almost seven-fold from a country with close to 100 million people to one with 670 million.

Mind-set change

This surge in potential market multiplies the possibilities for any country in terms of possible expansion. In order to maximize the gains that can be derived from an enlarged free trade area, a major mind-set change is required if a country begins from a background of protectionism, and high-tariff and nontariff regimes.

Philippine companies now have a much larger field of economic vision. It means that enterprises of other nations seeking new places of economic opportunities see larger market possibilities for their activities. When the enterprises of different nations seek economic and investment opportunities in one large market, it is inevitable that the degree of competition increases.

Despite the advance of Asean economic cooperation, the member-countries consider themselves independent countries with their own external economic policies, including investment incentives for foreign investments. Competition in investment attraction has been the rule among the countries as they developed their own economies.

In this setting, countries that have practiced open trade regimes with the world have a great head start. Little adjustment is required of them. Their firms are more trade-oriented and are likely to be more competitive.

Such countries gain enormously from the market expansion. A country with practically no tariff barriers like Singapore becomes a big winner. Those countries with fairly modest rates of protection from the external world are also big winners.

Malaysia and Thailand, which had relatively low protection rates before and whose investment climates had been relatively free and open to foreign investments, become winners as well. Investment flows into these countries have been high before and have continued.

Initially, Indonesia had one of the most protectionist regimes in the Asean. In fact, it resisted early efforts to broaden the early preferential tariff agreements. But in 1987, Indonesia undertook earnest reform efforts in industry to open the economy to more competition. Its huge natural resources sector has been relatively more open to FDIs than that of the Philippines even in earlier years.

As Afta came into being, Indonesia was able raise the scale of FDIs flowing into the sectors of industry, agriculture and natural resources.

Our gains from Afta as a country are not as evident as those of other Asean members yet. But we have great opportunities, too. To win big, we have mountains of economic policy problems to overcome.

These problems hinder our gains: (1) Philippine production involves high unit cost due to (a) the country’s labor market policies, with our high average wages due to minimum wage and other advanced labor legislation; (b) relatively poor infrastructure investments; and (c) corruption that adds to transaction costs. (2) There is a faulty investment incentives system that acts as barrier to foreign direct investment from our shores and drives it to our Asean partners.

The elevation of the country’s credit rating to “investment grade” does not solve the problems that we face competitively in the Asean. Policy makers need to recognize that many problems do not get solved without taking concrete steps to deal with them.

DTI, wake up

Let me elaborate on the faulty investment incentives problem. It hits the heart of the Philippine lag in FDI performance. The investment incentives system has remnants of the protectionist regime of the past with an ever-staying presence in our national psyche.

With Afta, there is no more domestic economy to think of. We have to think of an Asean-wide free market. Yet, our mainline investment incentive system is still couched in terms of safeguarding the domestic economy from foreigners. Our Department of Trade and Industry leaders need to wake up!

We operate current investment incentive policy on a dual front. Board of Investments (BOI) policies protect Filipino enterprise in the local market. Our main weapon for attracting foreign investment enterprises is through the export processing zones, which are administered by the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (Peza).

Peza policies were formulated to overcome the country’s excessively inward-looking policies of nationalistic industrial protection.

These two policies leave a big gap in our present economy. Peza firms do not have much to do with BOI industries. These firms obtain their raw materials at world prices. They have no backward integration with supplier firms in the domestic economy as BOI rules on capital ownership and market orientations have barred them.

Also, BOI industries have remained small, inadequately integrated in production and Philippine market-oriented only.

Amend Constitution

This situation must be corrected. There is a way out of these many detailed problems to catalyze the process of integrating the economy with more foreign investments.

Mind-set change is important. The most effective measure to deal directly with all these problems is to amend the restrictive economic provisions of the Philippine Constitution. All other measures are circuitous and likely to be patch-up solutions to the problem that we have.

(Editor’s Note: The author is professor emeritus of the University of the Philippines School of Economics, and was among the first to receive the UP President Edgardo J. Angara Fellowship Award. He was the country’s lead economic minister in 1976-1981 when the Asean economic ministers began discussing toward forging economic cooperation agreements. He was then the director general of the National Economic and Development Authority.)

RELATED STORIES

What’s going to happen in 2015? Nothing, says minister about Asean Integration

Purisima: No big bang for ‘One Asean’ in 2015