With oil smuggled in, gov’t waves tax revenues goodbye

MANILA, Philippines—The government may be losing at least P32.85 billion a year in tax revenue from unreported fuel retail sales, based on recent pump prices. This estimate can grow bigger with additional price increases since the value-added tax (VAT) component of the revenue, apart from specific taxes, will also increase.

From 1990 to 1997, oil industry demand saw steady growth, reaching a peak of 385,000 barrels a day in 1997. Starting 1998, with the industry fully deregulated and new players entering the market, stakeholders expected a steady rise in oil demand, especially when the economy grew by leaps and bounds.

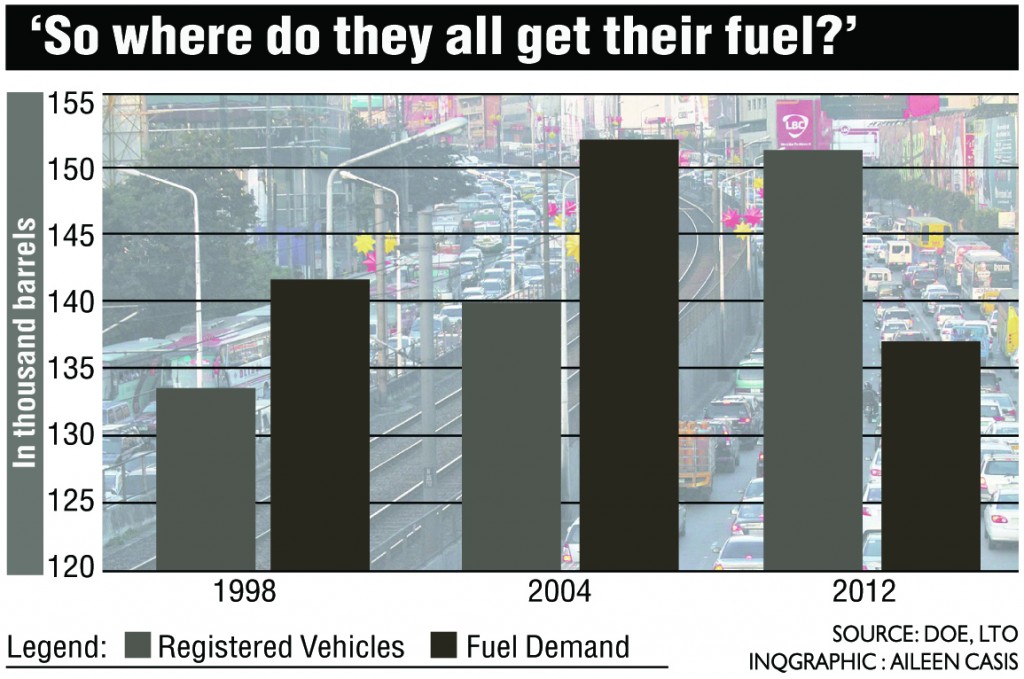

Yet, oil demand dropped by 20 percent to 303,000 barrels a day in 2012 compared with 377,000 barrels a day in 1998. Reported retail volumes alone, which could be directly linked to the number of registered vehicles, dropped by 4.2 percent to 137,000 barrels a day in 2012 from 143,000 barrels a day in 1998.

Missing from state coffers

Oil demand dropped just as the number of registered vehicles on the road grew by 125 percent, according to Land Transportation Office data, while the country’s population increased by 33 percent between 1998 and 2012, based on National Statistics Coordination Board data.

Despite the price increases, demand for fuel increases over time. So where do some of the country’s motorists get the fuel for their vehicles?

According to data put together from various sources, the Philippines’ state coffers could be missing some P15.71 billion in revenue from diesel and P17.14 billion from gasoline.

The Department of Energy (DOE)—the agency that monitors fuel supply and demand—coordinates regularly with the Bureau of Customs (BOC).

“We send our reports to BOC as they have the mandate to apprehend smugglers,” Energy Secretary Carlos Jericho Petilla said in a text message.

Asked to comment on fuel demand trends, Petron chair and CEO Ramon S. Ang said in a text message that the government could enjoy the benefits of oil deregulation through higher revenue if it could minimize smuggling.

The ‘independents’

Independent oil players, which aim to corner half the fuel market before 2020, have not seen more curbs in this area. Independent Philippine Petroleum Companies Association chair Fernando L. Martinez, who also heads the Eastern Petroleum Group, said via text message that there had been cases filed before, but the oil group was still waiting for major developments.

According to the DOE, major oil companies Petron Corp., Chevron Phils. and Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corp. still account for 70 percent of the total demand for petroleum products. The independent oil players and so-called end-users, or those who directly import part of their oil requirements, account for the rest.

The “independents” include Phoenix Petroleum, Total Phils., Liquigaz, Unioil Petroleum Phils., Seaoil, Jetti, PTT Philippine Corp., Isla Gas, MicroDragon, TWA Inc.’s Flying V brand, Petronas, Filoil Gas Co., Prycegas, Eastern Petroleum and Ixion.

In 2013, the Philippine economy, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), grew by 7.2 percent—said to be the second fastest in Asia after that of China.

The rise in economic activity is usually accompanied by an increase in fuel consumption which, in turn, supports further expansion for commerce and industry.

As the cycle gains momentum, government revenue from fuel sales also tends to increase. However, when smuggling happens, the state coffers lose tax revenue that could have been used for housing, education, and vital infrastructure projects.

Why smuggling persists

Industry sources said oil smugglers would make a killing from their illegal activities. An ordinary service station dealer usually sees a profit margin of P1.50 to P2 a liter. But smugglers apparently can rake in as much as P13 a liter for gasoline and P7 a liter for diesel, based on current prices.

Industry data showed that retail volumes, or fuel products sold at service stations, reached 143,000 barrels a day, or 22.74 million liters, in 1998. A total of 8.3 billion liters were consumed that year alone. This was when there were 3.3 million vehicles and 2.7 million licensed drivers.

By end-2012, retail volume consumed was only 137,000 barrels a day, or 21.8 million liters. Throughout 2012, consumption stood at 7.9 billion liters. By that time, vehicle population stood at 7.5 million—125 percent up from 3.3 million in 1998. There were also 4.55 million licensed drivers—67 percent up from 2.72 million in 1998, according to LTO data.

Assuming the retail volumes increased by 50 percent—as opposed to the 125 percent in registered vehicles and 67 percent growth in the number of licensed drivers, from 1998 to 2012 to mirror the rise in registered vehicles—it could be estimated that 77,500 barrels a day (based on 2012 retail volume of 137,000 barrels per day), or 4.5 billion liters a year, could have gone unreported and classified as smuggled.

Plus VAT

Diesel and gasoline are the major products sold at fuel stations, accounting for 65 percent and 35 percent, respectively. Applied to the 4.5 billion liters of what could be smuggled fuel, this could translate to 2.92 billion liters of diesel and 1.58 billion liters of gasoline.

Applying average Metro Manila prices of P44.83 a liter for diesel by end-2013, plus VAT of P5.38 a liter, that could translate to P15.71 billion in revenue loss for the government in a given year.

For gasoline, an average price of P54.19 a liter, VAT of P6.50 a liter, and specific taxes of P4.35 a liter, that could amount to P17.14 billion of foregone revenue.

The Philippines’ gross domestic product has significantly increased from P3.3 trillion in 1998 at the start of full oil deregulation to P6.3 trillion in 2012—an increase of about 91 percent.

The increase in GDP has been driven by sectors that depend on petroleum products. Oil consumption tends to increase rapidly as economies expand.

Also, population growth is another factor that may raise oil consumption. The Philippine population in 1998 was 72.6 million, which significantly increased to about 96.2 million in 2012.

Yet, retail demand remained flat from 1998 to 2012 despite a 125-percent increase in registered vehicles and a 67-percent increase in licensed drivers over the same period.

In 1998, reported retail volumes already reached 143,000 barrels a day. Given more efficient engines, new fuel technology, oil price fluctuations, and consumer behavior, retail volumes should have increased since deregulation.

Considering that a portion of new vehicle registrations could be additional vehicles belonging to a single owner, and that a quarter of licensed drivers did not actually own vehicles, retail fuel demand could have at least increased by 50 percent, reaching 214,500 barrels a day in 2012.

Forms of smuggling

There is smuggling, and there is smuggling.

Industry experts say technical smuggling is done through a number of ways. But all generally entails the use of tampered or counterfeit cargo documents.

Some importers declare lower value for their shipments, thus paying lower VAT and excise taxes (for gasoline, it is P4.35 a liter; for Jet A-1 it is P3.37 a liter). Apparently, this can be done by faking or tampering invoices.

Some importers declare lower shipment volumes for petroleum products, resulting in non-payment of taxes for undeclared volumes.

Others misdeclare their shipments to avoid paying taxes. For example, gasoline may be misdeclared as diesel to avoid paying the specific tax of P4.35 a liter.

Outright smuggling, meanwhile, takes places when petroleum is brought into the country without reporting the shipments to BOC officials.

Another form is called high seas smuggling, which occurs mostly offshore, where officials have no jurisdiction and very little presence, if any.

Fuel products usually come from nearby countries, where petroleum prices are much lower due to government subsidies. These will then be resold in the country.

Indonesia and Malaysia, which are close to the Philippines and whose fuel come cheaper (due to their respective governments’ subsidies), are among those said to be possible sources of smuggled products.

Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand are also possible sources due to their proximity to the Philippines.

Bunkering is the process of loading fuel in a marine vessel. Under existing trade agreements, international vessels can refuel tax free to travel in and out of the country.

Smuggling happens when a local party sells the fuel intended for international vessels back to the domestic market. In extreme cases, the international vessel is just used in the bunkering permit without any volumes being supplied to the vessel.

Exclusive economic zones, or EEZ’s, grant exporters tax-free imports of petroleum products as long as the products are used within the zone or are re-exported.

Some firms allegedly use this privilege to import tax-free petroleum products and then smuggle these out of the EEZ.