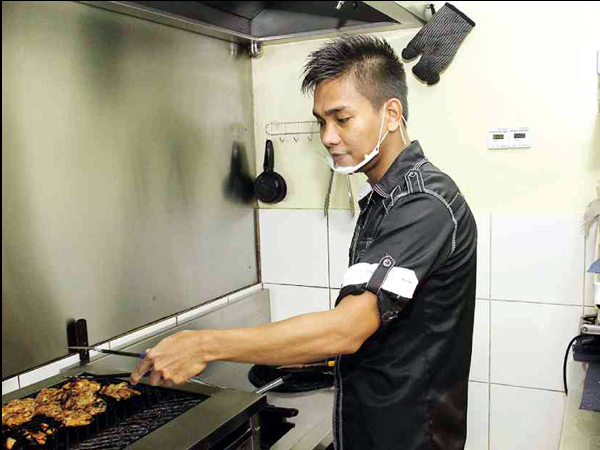

RICHARD Abrilla from gourmet griller to team leader (management trainee). No position is out of reach for the employee.

With no college diploma, Earl Chua began his career running an automotive shop that checked emissions. In his journey, he ventured into business process outsourcing and websites. Although he was gaining a reputation in Golf.Ph, the country’s No. 1 resource in the sport, Chua found his calling as a restaurateur.

“Everything has a purpose,” he declares. The 30-year-old chief executive officer of Faburrito Foods Inc. waxes philosophical that if it weren’t for his experience in owning an automotive business in his hometown, San Francisco (USA), he wouldn’t have had the guts to open a concept fast-food outlet in Manila.

“I’ve made money in the past. It isn’t my main motivation. For as long as I am comfortable, it’s enough that I can provide for myself, I would like to have a business that is making a difference.”

EARL Chua: “Our goal isn’t so much to generate revenue but to develop the brand and the culture that changes people’s lives.”

Faburrito isn’t the conventional Mexican restaurant. For one, it doesn’t serve the traditional, lard-addled refried beans. The black beans are home-made and freshly made from a pressure cooker. The nachos are infused with moringa. Instead of liquor and soft drinks, it offers specialty iced teas and fruit smoothies without the deadly sugar. Soft Christian music wafts in the air.

Born in San Francisco to Chinese-Filipino émigrés, Chua took up a vocational course at the Sequoia Institute and set up an automotive shop with his brother, Errol. With their savings and loans—and no help from the parents—they bought a struggling automotive shop for $120,000. In six months, their business, called Clean Air Smog, made a turnaround through aggressive marketing.

Seven years ago, Chua came to Manila to attend the funeral of his grandfather. He liked the Philippines and saw the potential to do business. His mother also had the foresight to get him a dual citizenship.

With his brothers, Errol and Erik, they ran a BPO and launched websites. As Chua spent more time in the Philippines, he sold his automotive shop.

“I decided to start my own business to justify my living here,” he says. “It’s easier to put up a business in the Philippines because it requires less capital.

Growing up in a multicultural city, he was exposed to authentic Mexican cuisine. “The burrito was invented in San Francisco,” he says.

Disappointed in the options of Mexican fare in the Philippines, Chua decided to set up a concept restaurant based on the Christian values on which he was raised. Keeping in mind on the impact of food on people’s lives, Chua decided that the fare should nourish the body and the soul.

“If you love somebody, you don’t want to serve something that would damage the health or make one fat. We wanted to create food that spread love and that the people felt good about serving it,” says Chua.

Inspirational quotes are printed on the take-out packages and napkins. In Faburrito outlets, the posters say that the ingredients are wholesome and that 10 percent of the customer’s receipt goes to charity, among them Real Life Foundation.

But the road to success wasn’t easy. “I was naïve. I thought I could hire somebody to run it. I would just come in and say, ‘This is my restaurant.’ It was more difficult than that,” says Chua.

With no consultant to guide him, the inexperienced Chua did everything from menu planning to staff training and even decorating. He gathered the recipes from the Internet and hired a cook to whip up the food.

“I had no idea about costing and standardization. I created an item on the menu and slapped on the price which I thought was fair,” he recalls.

He personally gave the pioneer employees lessons in English and personality development before they learned food preparation.

On the first year of Faburrito at The Columns on Ayala Avenue, the business was losing money. Chua admits it wasn’t marketed properly. He relinquished up his position at Golf.Ph to concentrate on his restaurant. Chua then hired chefs to improve the menu and teach food safety.

Among his ventures, he realized that the restaurant was the most challenging. “There are so many logistics and are very detailed. It’s all about margins. It’s inventory, spoilage, forecasting, sourcing, managing the people. To cut down on pilferage, our commissary in Taguig itemized all the items. The inventory is strict.”

Over time, Faburrito at The Columns started attracting a loyal clientele, mostly expatriates on weekdays. Chua explains that the recipes are so healthy that you can eat them daily unlike pizzas, hamburgers and fried chicken. A whole wheat burrito is less than 400 calories. People with dietarty restrictions can find an item on the menu to satisfy their needs. Diners can have their quesadillas customized.

The 70-seater Faburrito at The Columns attracts some 190 customers a day with an average receipt of P240 for a full meal. Some 40 percent of the business comes from take-outs. Smart telco invited Faburrito to open an outlet at the Smart Tower so that its employees can have a healthy alternative. The third Faburrito at Eastwood City Walk has established its own niche.

Another reason for Faburrito’s success is the employee satisfaction.

Instead of boring conventional job descriptions, the positions are given more honorable titles. Cooks are called gourmet grillers, the kitchen crew that prepares the food are referred to as appetite advisers. The cashier is the courtesy clerk, while the waiters/busboys are satisfaction specialists. The managers are considered coaches.

“We wanted to give positions that people can be proud of. At the same time, we have high expectations,” says Chua.

Although the team comes from diverse backgrounds—Catholic, Jehovah’s Witness and Iglesia Ni Cristo, they join the Bible studies. In pre-shift meetings, the employees are reminded of the company’s values-purposive team work, integrity, growth, excellence, giving back and respect. The sessions also include airing of concerns and a prayer.

“The prayer puts things into perspective. It reminds them of their goals,” says Chua.

“Everybody knows why they are here. They know that the more successful they become, the more successful the company will become. This will give more jobs and help other people. My team comes to work because they know they have a future and a reason for being here—to get better and to change lives. That is motivating for them,” explains Chua.

He cites Chester Alfaro, 22, the general manager, who started out as a management trainee three years ago as a success story.

Richard Kennette Abrilla, 26, the team leader at The Columns branch, started out as a “gourmet griller.” The pioneer employee spoke in pidgin English and had no knowledge of kitchen operations. He says he owes the company for improving his communication skills and developing his self-confidence.

Abrilla has seen how Faburrito has evolved from an unknown restaurant to a favorite in the blogs. ”Aside from healthy food, we give the customers the best service we can. They eat at Faburrito because they say the people are warm and friendly. It’s not something that is taught here. We inculcate it in ourselves,” he says in Tagalog.

Chua has learned to be diplomatic in dealing with the sensitive nature of the Filipino. Still, he has to balance it with discipline. He observes that apologizing for a mistake without any disciplinary action will not produce results.

“I nurture and explain why things are done in a certain way. I realized that you have to have everything structured. Otherwise you can get taken advantage of,” he says.

Plans are afoot for a new restaurant concept at the new Century City Mall. He hopes to own some 20 restaurant outlets that will support his CSR, the Fab Foundation.

“You can feel good about eating. What you’re eating is helping other people. The Fab Foundation’s goal is to provide scholarships for street children, and hopefully create a vocational boarding school that teaches skills.”