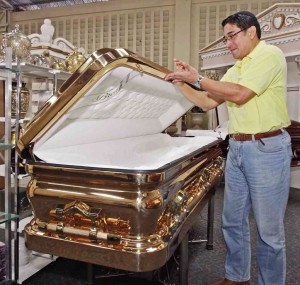

P1.8 MILLION 24 KARAT GOLD PLATED COFFIN: Robert Gregorio, chief operations officer, Cosmopolitan Funeral Homes Inc. shows their solid bronze 24 karat gold plated promethean casket. JUNJIE MENDOZA/CDN

The profession may be morbid, as you say, but it’s big business,” says a friend, confirming what is common knowledge and conjuring up scenarios on the high cost of dying. She was referring to some high-profile funeral houses, possibly franchised, which are part and parcel of what is now known as the death care industry.

Officially not part of the industry are the many parishes who offer mortuary services. In some of the upscale churches, the tables are set up as in a banquet, and the food caterers make a killing (double-entendre and possible irreverence not intended).

These funeral houses-crematoriums are run like a corporation, with life plans, packages, benefits, product development, services, and perhaps a dash of CSR (corporate social responsibility).

The leading death care companies include St. Peter Memorial Chapels, Loyola Memorial Chapels & Crematorium, Arlington, Nacional, Sanctuarium and La Funeraria Paz (the last four, for some reason, are all located on Araneta Ave., Quezon City).

St. Peter was founded by the late Francisco M. Bautista (1914-1996) and has been in the business for more than 30 years. The company operates an “elite” memorial chapel in Quezon City, Cebu City and Davao City. There are also memorial chapels in Sta. Mesa, Manila and in Alabang, Metro Manila, along with more than 200 chapels nationwide.

“We have different plan types that suit your budget and are payable in cash or installment for a period of five years,” says a St. Peter spokesman. And he did not entertain any further questions.

A corporate profile of the firm describes an “e-Burol” service which will enable relatives and friends who cannot go to the wake to view the remains anywhere in the world through this website. The facility entails a user-name password which will be provided only to the family.

Among the CSR projects of St. Peter, the corporate profile notes, are “Gift for Angels” (free memorial services for infants three months or younger), and Memorial Gift Certificate for “outstanding” persons.

Loyola Memorial was founded in 1972 by the late senator Gil Puyat and is part of the Loyola Group of Companies, which includes the Loyola Life Plan. “Funeral Services are priced to suit any budget,” says a spokesman. “Clients can discuss with the staff and management their requirements and needs, so that a package with specific needs can be drawn up.”

The main Loyola chapel along Edsa Guadalupe Viejo is a familiar landmark in Metro Manila. Available are “Premier” and “Super Deluxe” chapels.

How expensive is it to bury a relative?

A friend who recently buried a close elderly relative spent P80,000 for a four-day wake with free coffee and water, Wi-Fi in the chapel, coffin for viewing, two flower arrangements and cremation.

That was in Olongapo City. Presumably it will be more expensive in Metro Manila because the “competition” is keener.

Plastic coffins?

Ideas-man Isidro C. Valencia, whose letters to the editor appear from time to time in the Inquirer, suggests that death care specialists can bring costs down by having plastic instead of the usual wood coffins.

“If the coffin is plastic mawawala ang (no) oxygen, the bacteria will die and the body will decompose less rapidly,” says Valencia (elcidvalencia60@gmail.com). He has talked to embalmers in Cagayan de Oro City and they are sold on the idea, according to him.

Shifting from wood to plastic will entail a mold, which is available in plastic companies. This is expensive but with economies of scales, says Valencia, “the price of a coffin will be lowered by 50 percent.”

Is the suggestion workable? Will the “captains of (death care) industry” embrace the idea or will they consider it déclassé? Will it reduce profits?