Updated Edition, 2013

by Hywel Williams

Quercus, London

Usually, the headlines we watch, hear or read at any time of day come alive when there are quotes from “talking heads”—as editors call them. The narrative, told in the third person, suddenly acquires a sense of freshness and immediacy.

On television, the talking head is “on-cam,” another shorthand for the TV camera focused on the subject. On radio, he or she is “delivered” as sound bites. In print, the subject’s words are set off in quotation marks—a signal to the reader that he is getting first hand the version—or vision—of the maker of news!

Suppose you are treated to a much longer, face to face, encounter with what we call the “movers and shakers of society”—if not the movers of the world? You have a ringside view of—or you are within hearing distance from—the eloquent words of this charismatic celebrity (or a much-maligned personality). Then, you set aside the interpretation of the reporter and get it direct “from the horse’s mouth”.

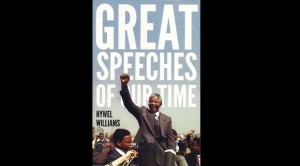

This is the sense I got from reading the “Great Speeches of Our Time,” selected, edited, and annotated by historian, journalist and television host Hywel Williams. What I have is a paperback edition, 310 pages, of the book. It was first published in 2009, and updated in 2013 to include the victory speech of second termer Barack Obama.

The book serendipitously chose the “universally admired” Nelson Mandela as book cover. Mandela’s passing only last month made headlines and was mourned by leaders around the world. The venerable Mandela was rediscovered, his thoughts revisited, and his resonant leadership style, marked by magnanimity, was learned and relearned by students of leadership across the globe.

The reader’s real treat to have on hand are Mandela’s two speeches in this book—one delivered in 1964 when Mandela declared that he was “prepared to die” for the cause of ending apartheid in South Africa; and the other, delivered in 1994, a historic moment, when he cast a vision of “a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.” In his inaugural speech, Mandela wax poetic:

“To my compatriots, I have no hesitation in saying that each one of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees of Pretoria …

“We are moved by a sense of joy and exhilaration when the grass turns green and the flowers bloom.” This is not the voice of a bitter man whose youth and strength were wasted in prison for many decades. He continued:

“Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world.”

Mandela’s voice was surely beyond flowing rhetoric. He matched word with deed: He invited his former oppressors, jailers and persecutors to share the task of rebuilding South Africa.

There is another icon in contemporary history who made his mark, this time in the more familiar American continent.

Barack Obama’s victory address after being reelected President of the United States is likewise in the book. The notes of author Williams are at times as breathless and as eloquent as the speeches in the book—like this one about the first black American President:

“Confronted by a stuttering economy that never quite seemed to respond to the stimulation measures that he applied, intransigent resistance to a controversial healthcare reform bill that had to be wrenched into law and a Republican-dominated legislature that regarded obstruction rather than constructive governance as its animating principle, Barack Obama seemed in danger of joining the ignominious ranks of America’s one term presidents.”

As stunning history would have it, Obama won a second term from a close electoral contest, graphically described by author Williams as: “The rival candidates were rarely separated in the polls by anything more than the width of a cigarette paper.”

The triumphant moment did not escape Obama when he concluded his victory speech in Chicago in the evening of Election Day in 2012:

“I believe we can seize this future together because we are not as divided as our politics suggests. We’re not as cynical as the pundits believe. We are greater than the sum of our individual ambitions and we remain more than a collection of red states and blue states.”

This book of 40 speeches spanning 70 years also features poets, artists, civil society leaders, feminists, civil rights advocates, military commanders—and even authoritarian heads of state—meaning, dictators.

The author is quick to add though that most of the “orators,” as he calls them, have assumed leadership positions through democratic means. “And their words,” said Williams, spoken by and large at the very apex of their influence, reflect a career-long training in the art of eloquent persuasion.”

This “art of eloquent persuasion” is very evident in the speeches of political leaders like Winston Churchill and Tony Blair of England, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Mario Cuomo of the United States, Pierre Trudeau of Canada, Charles de Gaulle of France, Jawaharlal Nehru of India, David Ben-Gurion of Israel, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, and Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR.

We all know the epic influence of Churchill in turning the tide of war for the Allied Powers against the German-led Axis alliance. When England stood alone fighting the blitz of Nazi forces, Churchill’s voice is heard on the radio airways. Reflecting on his role during that tense period when victory was yet unsure, Churchill said: “It was the nation and the race dwelling all round the globe that had the lion’s heart: I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar.”

The book featured Kennedy’s three speeches, highlighting the effective and instructive rhetorical devices used by Kennedy’s speechwriter, Theodore Sorensen.

Outside of government and yet influencing state policies were the speeches of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, environment advocate Anita Roddick, Irish poet Seamus Heaney, and Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk.

King’s “I Have a Dream” address is fortunately included in this book anthology, giving our readers a taste of a soaring eloquence that takes off from the language cadence found in the Bible and the upbeat rhythm of Negro spirituals (when “Negro” was not yet a bad word).

It would be refreshing for the readers to enjoy the speeches of artists and poets— and see how the artist’s vision is made to bear on national or global issues affecting humankind.

On the whole, the book dishes out a double treat to you, our readers. First, you will enjoy the ringside advantage of reading and listening to the speeches; and, second, you can imagine the heat and passion of the times where and when they were delivered.

Significantly, many of the speeches highlighted in this collection changed the course of a country, a continent or even the world.

Some were clearly intended consequences. The black people had been emancipated as espoused by the civil rights movement led by King and his co-leaders. The structure of apartheid was dismantled, and a black-dominated leadership was installed in South Africa.

One was an unintended consequence. When Gorbachev spoke of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), the states under the Soviet Union began to embrace such liberating concepts. And so in one exciting period in history, the USSR collapsed—and thus emerged independent states from the rubble of a Union held together for so long by iron rule.

You will expect to be more informed and wiser after you read the speeches in this book, and then get the insight and perspective on how such words changed some parts of this world—or our common world itself.

As you read through the speeches, you, our readers, will agree with me if I conclude this with a paraphrase of a familiar saying: “The spoken word is mightier than the sword.” (dmv.communications@gmail.com)