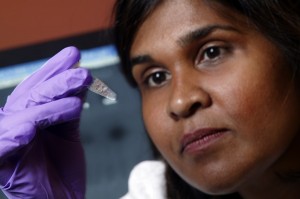

This undated image provided by Johns Hopkins Medicine shows Dr. Deborah Persaud of Johns Hopkins’ Children’s Center in Baltimore. The new report, published online Wednesday Oct. 23, 2013, by the New England Journal of Medicine, makes clear that a girl, now 3, was infected in the womb. She was treated unusually aggressively and shows no active infection despite stopping AIDS medicines 18 months ago. Persaud helped investigate the case. AP PHOTO/JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICINE

WASHINGTON—Modern medicine can keep HIV at bay but not cure it, and researchers said Thursday the reason may lie in the larger-than-expected size of the virus’s hiding place.

Traces of HIV can lie dormant in the body’s immune cells, and this so-called latent reservoir is 60 times bigger than previous estimates, according to new research in the journal Cell.

The findings, based on three years of lab experiments, explain why human immunodeficiency virus usually makes a swift comeback and can lead to full-blown AIDS if an infected person stops taking antiretroviral drugs.

“Our study results certainly show that finding a cure for HIV disease is going to be much harder than we had thought and hoped for,” said senior investigator Robert Siliciano, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Siliciano in 1995 first showed that reservoirs of dormant HIV were present in immune cells.

There are 213 known proviruses, or remnants of HIV, that linger in cells and tissues throughout the body even when HIV is undetectable in the blood.

The latest research showed that 25 of these—a total of 12 percent—could reactivate themselves, replicate their genetic material and infect other cells.

This came as a surprise to the science team, because these non-induced proviruses had previously been viewed as defective, therefore playing no role in the infection’s return.

The study found that the average frequency of intact non-induced proviruses was “at least 60-fold higher” than the potentially dangerous latent viruses that scientists already knew about.

All these intact non-induced proviruses need to be wiped out in order to achieve a cure, experts say. What is needed are specialized drugs that target them.

More than 34 million people worldwide are infected with HIV. The three-decade-old pandemic kills about 1.8 million people each year.

A handful of people with HIV around the world have been described as being in remission or potentially cured of HIV, but these cases are rare.

The most famous of them, Timothy Brown—an American who was long referred to as the Berlin patient—was cleared of the virus after a bone marrow transplant that wiped out both his leukemia and his HIV infection

Another novel case involves a young girl who was infected in the womb, and was given a potent dose of antiretrovirals shortly after birth until she was 18 months old.

At that point, the child’s mother stopped bringing her to the doctor and stopped giving her medication. Research out Wednesday showed the now three-year-old child has no trace of HIV in her blood despite going 18 months without treatment.

Clinical trials to test the approach on a wider scale in infants in low and middle income countries are set to begin next year.

“Although cure of HIV infection may be achievable in special situations, the elimination of the latent reservoir is a major problem, and it is unclear how long it will take to find a way to do this,” said Siliciano.—Kerry Sheridan