Filipinos shifting from ‘sari-sari’ stores to supermarkets

It may be too early to pronounce the sari-sari store industry dead, but Filipinos’ shopping habits are definitely changing along with the times and the surging economy.

According to the results of a survey conducted by international market research firm Nielsen, local buying habits— especially for grocery items— are also changing rapidly because of the proliferation of supermarket chains which are growing their branch networks to cover areas previously served only by “mom and pop” convenience stores.

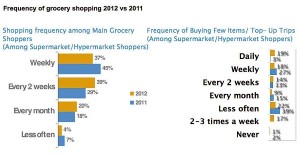

More importantly, the Shopper Trends Report released by Nielsen revealed that many Filipino shoppers now opt to shop with smaller baskets but with more frequency rather than buy in bulk.

“The preference to these smaller but frequent shopping trips is brought about by the close proximity of the supermarkets to the homes,” says managing director of Nielsen Philippines Stuart Jamieson in an interview with SundayBiz.

Whereas Filipinos used to secure their day-to-day household item needs from neighborhood sari-sari stores, many have now begun to move to supermarket shopping for the supply of their essential items.

Because of this promixity of supermarkets to homes, people now find it more convenient to make frequent short trips for their grocery needs, as opposed to the previous practice of visiting the grocery only once a week or even once a month.

Nielsen’s Shopper Trends Report is an annual study of consumer shopping behavior conducted in urban locations across the country. The latest edition of the study was made during the fourth quarter of 2012, through interviews of almost 2,000 respondents aged 15 to 65 years.

According to the company, respondents represented consumers from the A, B, C, D and E socioeconomic classes who were either main decision makers or key influencers when it comes to household grocery shopping.

The latest findings present a potential gold mine for supermarket chains who can take advantage of Filipinos new shopping habits.

The study also found that, on the average, Filipino shoppers replenished their pantries from three times a month to two times a month, while smaller but more frequent shopping trips were done seven times in a month, up from three times in 2011.

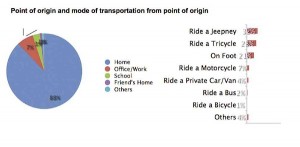

The presence of supermarkets near residential areas is a primary influence in this shopper behavior. Filipino shoppers say that they prefer supermarkets that are easily accessible from their homes via jeepney, tricycle and even by foot.

The Shopper Trends Report say that while grocery shopping continued to be a planned activity and shoppers came equipped with a shopping list, nine out of 10 shoppers admitted that they end up buying more than what they ought to.

“There is a lot of impulse buying that goes on with these frequent short trips to the grocery,” says Nielsen’s executive director for consumer insights Lou Ann Navalta. “This is also an opportunity for the retailers.”

In the report, respondents also reveal that that they increased their monthly spend on food, grocery and personal care by eight percent in 2012.

“The perception of shoppers that prices have stabilized plus factors such as introduction of new products or brands and promotions made sticking to the shopping list a challenge,” Jamieson points out.

In 2012, the proportion of early adopters or those who look out for new brands and products increased from nine percent to 15 percent.

Three out of 10 shoppers are promotions driven, although for brands that they already like.

The Nielsen official cautions, however, against writing off the local sari-sari store industry with the advent of large supermarket chains.

According to Jamieson, the iconic neighborhood sari-sari store will continue to be a fixture in small communities all over the country, because they serve an important social role that supermarkets cannot replace.

In addition to being situated closer to homes, sari-sari stores also serve as extensions of the home pantry sometimes, where consumers can rush to when a sudden shortage of soap, shampoo, toothpaste of cooking oil emerges.

But there will definitely be less sari-sari stores around in a few years, Jamieson says.

“Instead of nine sari-sari stores in a single community, maybe there will only be three,” he predicts.

While there is a strong sentimental attachment among Filipinos for their old reliable sari-sari stores, many among the younger generation are increasingly attracted to modern supermarkets—now suddenly more accessible in their neighborhoods—which offer convenience, safety and a clear, airconditioned environment.

Clearly, sari-sari stores who want to survive the coming convenience store shakeout must adapt … or perish.