It’s awards season again.

Local, regional and global creativity award shows will announce the winners in a few weeks. Part and parcel of these heady nights are gnashing of teeth, and occasionally, scandals that lead to seeing heads roll.

Who doesn’t want to win a Cannes Lion or Clio?

Last week, just as people thought scam ads were a thing of the past, they made a return.

Social media was abuzz with, according to Ad Age, “a ridiculous creative work that has gotten an agency and its corporate client in trouble.”

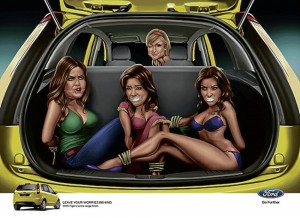

The campaign at the center of controversy was done by JWT India—posters showing women tied up and gagged in the trunk of a car brand.

One of the ads depicts a bikini-clad Kim Kardashian and her sisters Kourtney and Khloe gagged at the back of the vehicle while Paris Hilton winks at the driver’s seat.

The agency uploaded the ads in “Ads of the World,” a favorite website of advertising creative people that showcases real and ghost work from all parts of the globe. What ensued was a litany of backlash.

The agency also entered the work in India’s Goafest Ad Festival. As judging was ongoing, the agency’s chief creative officer withdrew the ads, but it was too late, the damage had been done.

For his part, the car brand’s senior officer for global marketing was forced to start his speech at an international auto show apologizing for the car’s sexually offensive ads.

Four days after, the agency’s head of creative, along with the senior creative director on the account, was asked to resign. The car brand’s office in India also fired a senior executive whom it didn’t name.

In 2006, JWT India almost won a Cannes Print Grand Prix for its Levi’s campaign—a series of stick figures with a signature red “Levi’s” tab stuck to their legs. The only copy said: “Slim Jeans.”

The unfortunate turn of events led Ashish Bhasin, Aegis Media chair and CEO, southeast and south Asia to say:

“The distasteful portrayal of women, coming at a time when India was in the process of putting a law to prevent violence against women, has put the creative agency and client in damage control mode.”

Filipino Executive Creative Director Eric Cruz of Leo Burnett Malaysia, who is coming this month to speak in Creative Guild’s “Kidlat Awards,” shares his views on scam ads:

“Scam ads are getting harder and harder to recognize against real ads these days, they’re getting more sophisticated,” he says.

Cruz steered LB Malaysia to the top of the rankings in Asia Adfest last month, where Leo Burnett won Agency Network of the Year.

“At the end of the day, any work that’s not done for a client is, in my book, “student work,” created without client’s confines and budget constraints. It is the equivalent of concept work, visionary but not real,” he says.

Scam ads around the world

Scam ads are known as “truchos” in Spanish, and Brazilians call them “fantasmas” or ghost ads. Before 1996, it was totally unheard of in the Philippines.

In 2009, organizers of the 3rd Dubai Lynx Awards uncovered a large cache of bogus ads from entries submitted to the competition, subsequently withdrawing the Agency of the Year award from ad agency FP7 Doha.

Seven previously handed out awards were rescinded: 1 gold (print campaign), 1 gold (TV/cinema campaign), 3 silver (print campaigns), 1 silver (outdoor campaign) and 1 bronze (TV/cinema campaign).

Additionally, 10 pieces that were short-listed in print and outdoor categories were also disqualified.

At the height of the scandal, Sunny Hwang, president of Samsung Electronics Levant, made the following statement to the public:

“At no time was Samsung Electronics aware of these advertisements and the company has not approved or commissioned FP7 to create any advertising campaigns.”

An ad for Taronga Zoo in Sydney was perhaps the most high profile ghost ad that got caught in 2000. The Cannes Lion that it won was withdrawn after organizers found out that the zoo did not authorize the winning agency to do the ad on their behalf. The creative director of the ad was dismissed.

Five years ago, a made in Brazil poster enraged Americans. The ad purportedly created for the World Wildlife Fund was much-reviled ad because it showed a fleet of planes flying toward the New York Twin Towers.

To make the matter even worse, the ad was found to have run only once in a small Sao Paolo newspaper. It won a One Show merit award but organizers have since withdrawn the award.

In 2002, Brazilian independent ad agency DPZ Propaganda scored two gold Lions for a lubricant gel brand. In a statement, the makers of the product said the ad “was created without the involvement or approval of any of the company’s employees.”

A couple of years ago, a Southeast Asian ad agency won a gold and silver Lions in Cannes, making it the most awarded Asian agency.

But victory celebrations were cut short. The agency found itself embroiled in controversy parrying accusations that it won with a scam campaign for a beer brand. To this day, the industry remains skeptical and is unconvinced by the agency’s explanation.

Measures against scam

In an unprecedented move to stem the problem, One Show, one of the world’s four toughest ad awards, implemented new rules in 2008, to ban agencies and members of creative teams found guilty of making fake ads for a period of five years.

“We need to protect One Show and the industry from losing credibility. It’s time to stop this bullshit. The purpose of awards shows are rewarding great work for a brand, not work created for awards shows,” Kevin Roddy, One Club chair, says.

The world’s toughest awards show D&AD joined One Show in taking a strong stance against scam ads.

“Work must have been produced in response to a genuine brief and be approved and paid for by the client. Works created solely for the purpose of entering competitions are not eligible,” it announced.

Cannes, the world’s biggest advertising festival, has this to say:

“The role of Cannes Lions is to celebrate creativity and to reward the industry for outstanding creative work. Our role is not to come between the client and the agency, not to have a negative material effect on agency business and not to penalize individuals from an agency who have not had any association with the work in question.

But it takes a hardline and says: “Our key rules are simple: Entries cannot be made without the prior permission of the advertiser/owner of the rights of the advertisement. All entries must have been made within the context of a normal paying contract with a client. That client must have paid for all, or the majority of, the media costs.”

In light of the JWT India incident, Ad Age ran a survey among top agency chief creatives on what the industry should do about it.