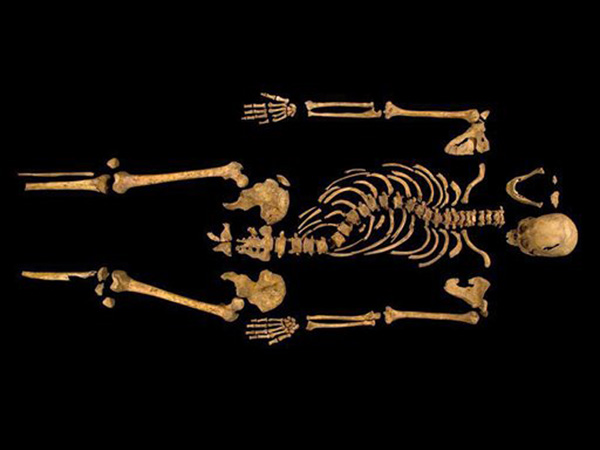

Undated photo made available by the University of Leicester, England, Monday Feb. 4 2013, of the remains of England’s King Richard III, missing for 500 years. The identification of the skeleton is the latest coup by forensic scientists who use radiocarbon-dating, DNA analysis, 3D scanning and other hi-tech tools to unlock the secrets of the long-dead. AP/ UNIVERSITY OF LEICESTER

PARIS—The identification of King Richard III’s skeleton is the latest coup by forensic scientists who use radiocarbon-dating, DNA analysis, 3D scanning and other hi-tech tools to unlock the secrets of the long-dead.

Other famous cases include:

— OETZI THE ICEMAN

In 1991, hikers in the Oetztal Alps in Italy’s Tyrol region found the mummified remains of a man that had been extraordinarily preserved by the ice.

Since then, scientists have uncovered that “Oetzi” lived 5,300 years ago, died at the age of about 45, was 1.60 meters (five foot, three inches) tall, weighed 50 kilos (110 pounds), had brown eyes and brown hair… and was probably allergic to milk products.

He was shot in the back with an arrow but lived for some time after his fatal wound, according to atomic microscope images of blood cells.

— LOUIS XVI

In December 2012, scientists from Spain and France authenticated the remains of a rag said to have been dipped in the blood of France’s last absolute monarch after his beheading in January 1793.

They linked DNA found in the sample, kept in an ornately decorated vegetable gourd, to another gruesome artefact: a mummified head believed to belong to Louis’ 17th century predecessor Henri IV.

The rare shared genetic signature gave firm evidence for authenticating both sets of remains.

— HENRI IV

The revolution in which Louis and queen Marie-Antoinette lost their heads also saw mobs ransack the royal chapel at Saint-Denis, north of Paris. Ancient monarchs like Henri were hauled from their tombs, defiled and thrown into a pit.

An individual was recorded to have rescued a severed head from the chaos, allegedly that of “Good King Henri,” famous for promoting religious tolerance but assassinated by a Catholic fanatic in 1610.

In 2010, scientists found proof that the head was Henri’s, citing physical features that matched 16th-century portraits, radiocarbon dating, 3D scanning and X-rays.

— LOUIS XVII

Pathologist Philippe Charlier, dubbed the “Indiana Jones of the graveyards” by French media, used genetic data in 2000 to determine that a mummified heart held in a glass urn came from the uncrowned son of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

The lad died in prison during the French Revolution. A doctor removed his heart and smuggled it out of the jail in his handkerchief.

In 2000, a DNA match was found between the heart and locks of hair from Marie-Antoinette, her two sisters and DNA samples from two of the sisters’ living relatives. In 2004 the heart was buried alongside the bodies of his parents.

— RAMSES III

Scientists said in December 2012 that an assassin had slit the throat of Egypt’s last great pharaoh at the climax of a bitter succession battle.

Hieroglyphs show that the wife and son of Ramses, who ruled from 1188-1155 BC, were convicted of plotting his death.

No evidence had existed that the plan was carried out until the experts announced last year that computed tomography (CT) imaging of the mummy revealed the pharaoh’s windpipe and major arteries were slashed.

— NAPOLEON

For years, maverick historians in France argued that Napoleon Bonaparte had been poisoned by his English captors during his final exile on Saint Helena.

Scientists from Switzerland, Canada and the US trawled over a doctor’s diagnosis of the patient and an autopsy conducted after the emperor died.

The verdict in 2007 matched that of 1821: “Boney” died of stomach cancer brought on by an ulcer.

— JOAN OF ARC

Bones venerated as the remains of France’s patron saint, authenticated in 1909 by a papal commission, came in fact from an Egyptian mummy and a cat, Charlier found in 2007.

He enlisted the help of two leading “noses” in the French perfume industry to help his investigation.

They smelled hints of vanilla in the relics—a useful tip, as the molecule vanillin is produced when a body decomposes, thus not someone who was burned.